How Ransomware Gangs Use Phishing to Intercept Logins

Phishing remains among the foremost cybercrime tools for cybercriminals, according to the FBI’s 2024 Internet Crime Report, which tops the list ahead of extortion and personal data breaches. But how are victims still falling for these attacks?

When I boot up my machines, I treat their internet access like entering a digital battlefield, because all connected devices exist within an interconnected web spanning a vast global warzone.

I am a former cybercriminal, although unlike ransomware groups, I didn’t steal money or files; I stole access. I relied on self-built phishing kits in order to hijack anything unsuspecting users typed in the input prompts.

Even though many of us know better than to click just any link, companies still fall prey to this old yet effective attack. That’s because they fail to treat internet-facing network devices as infrastructure operating on a digital battlefield.

Many sit at their workstations, coffee in hand, chatting with the person in the cubicle next to them as they type in their credentials to start their day. Any notion of accessing a battlefield is far from their minds because they don’t perceive the threats they may face that day.

They might not notice a subtle change in an outgoing purchase order, just a slightly altered account number, quietly diverting funds to a threat actor using stolen purchase order templates from a compromised vendor account.

How Fraudulent Webpages Phish Credentials

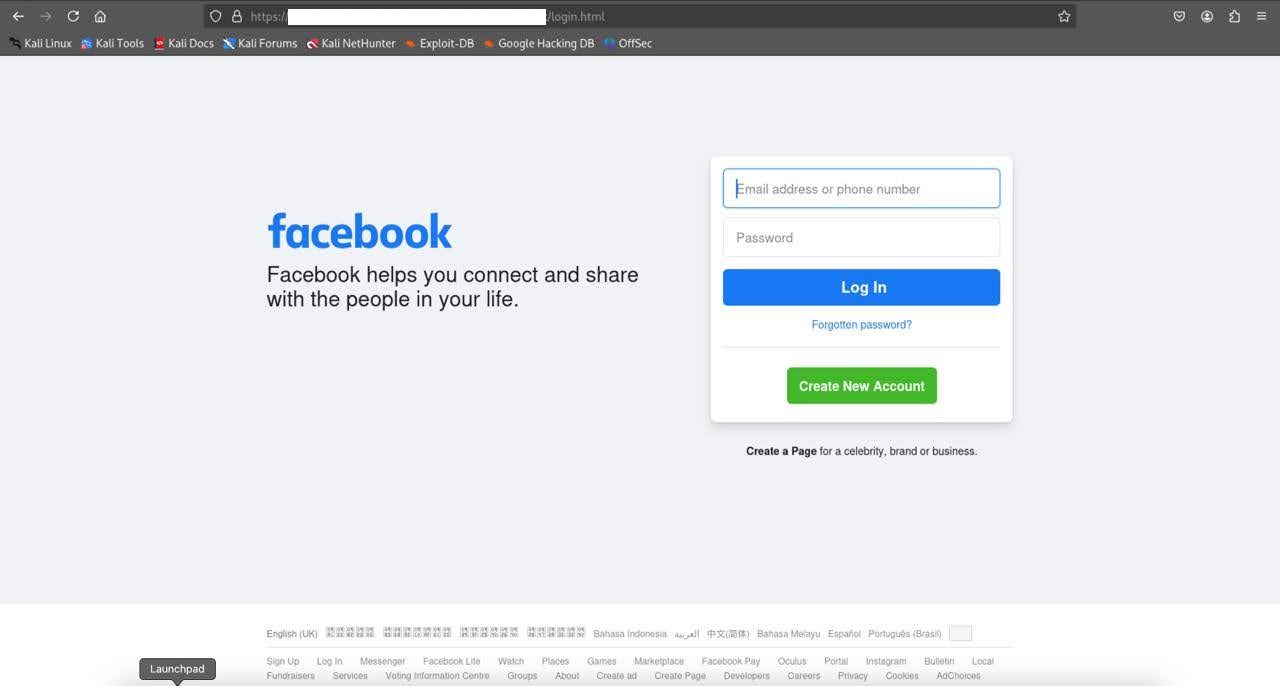

Cybercriminals often pick popular sites to clone. Pick a site you frequently visit, and there are likely hundreds, if not thousands, of sites impersonating it. Using a cloned front-end and an exfiltration endpoint by manipulating GET/POST queries, they capture the logins of those who don’t pay attention.

This is accomplished by copying the site’s HTML, PHP, CSS, and JavaScript of the login page they want to impersonate, along with the site’s image assets. Next, they host the site somewhere and purchase a domain name that appears similar or related to the site they’ve impersonated.

For example, facebook.com is the legitimate domain. Attackers may impersonate it with lookalike domains such as facebo0k.com, facebook-login.com, or fb-secure.com. Most phishing sites now use HTTPS, so the padlock is not proof of safety. HTTPS (Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure) is HTTP over TLS: it authenticates the server’s domain name via a digital certificate and encrypts the connection.

Check Domain Registration - the HTTPS Padlock isn’t Fool-Proof

However, a site having HTTPS does not guarantee the site is authentic. This means the padlock beside your browser’s web address bar doesn’t prove that a site isn’t cloned. If you’re familiar with the URL, you’re in the clear.

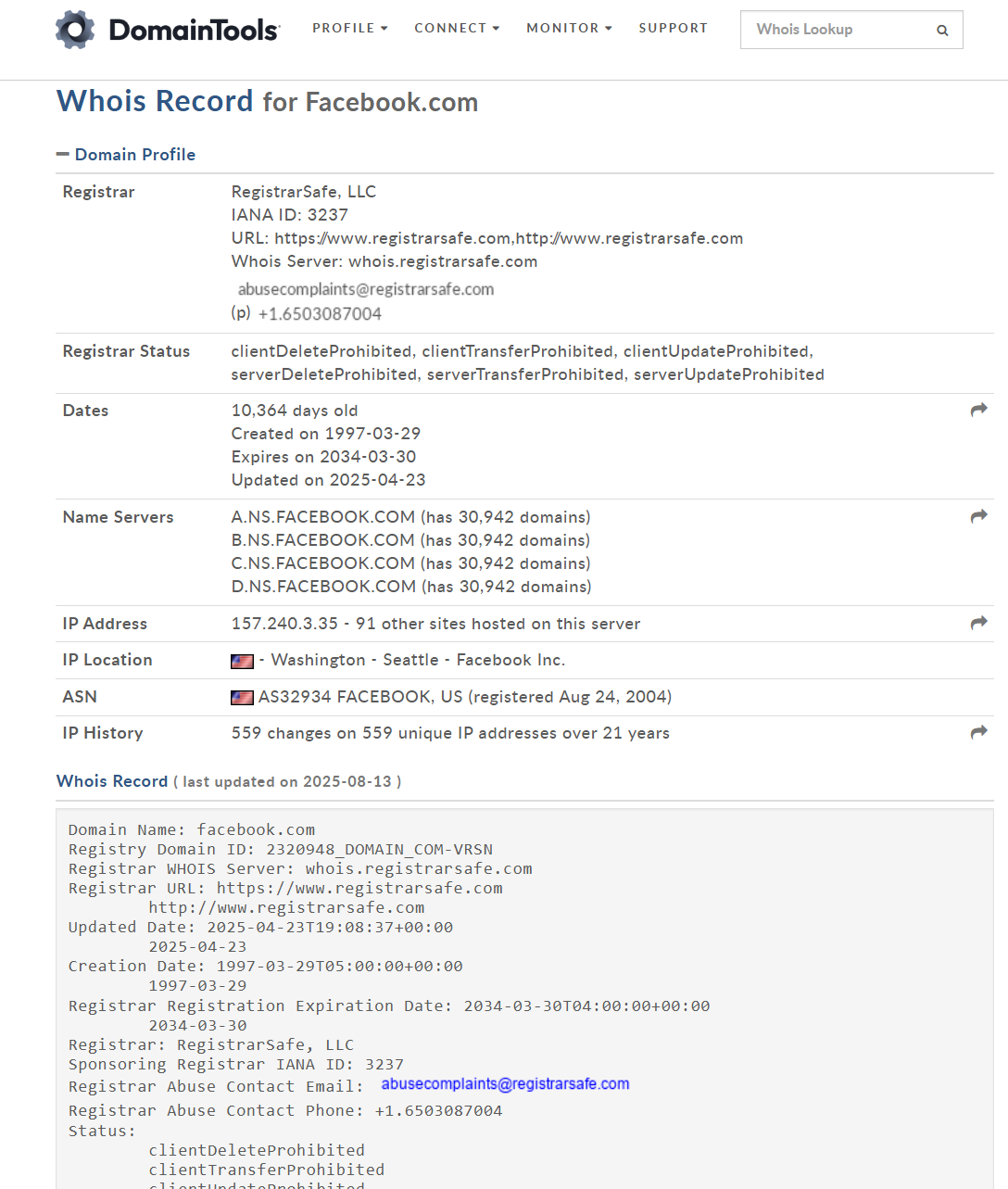

If you’re unsure, check the registrable domain. I have been using whois.domaintools.com for almost two decades now to inspect the domain registration of suspicious sites.

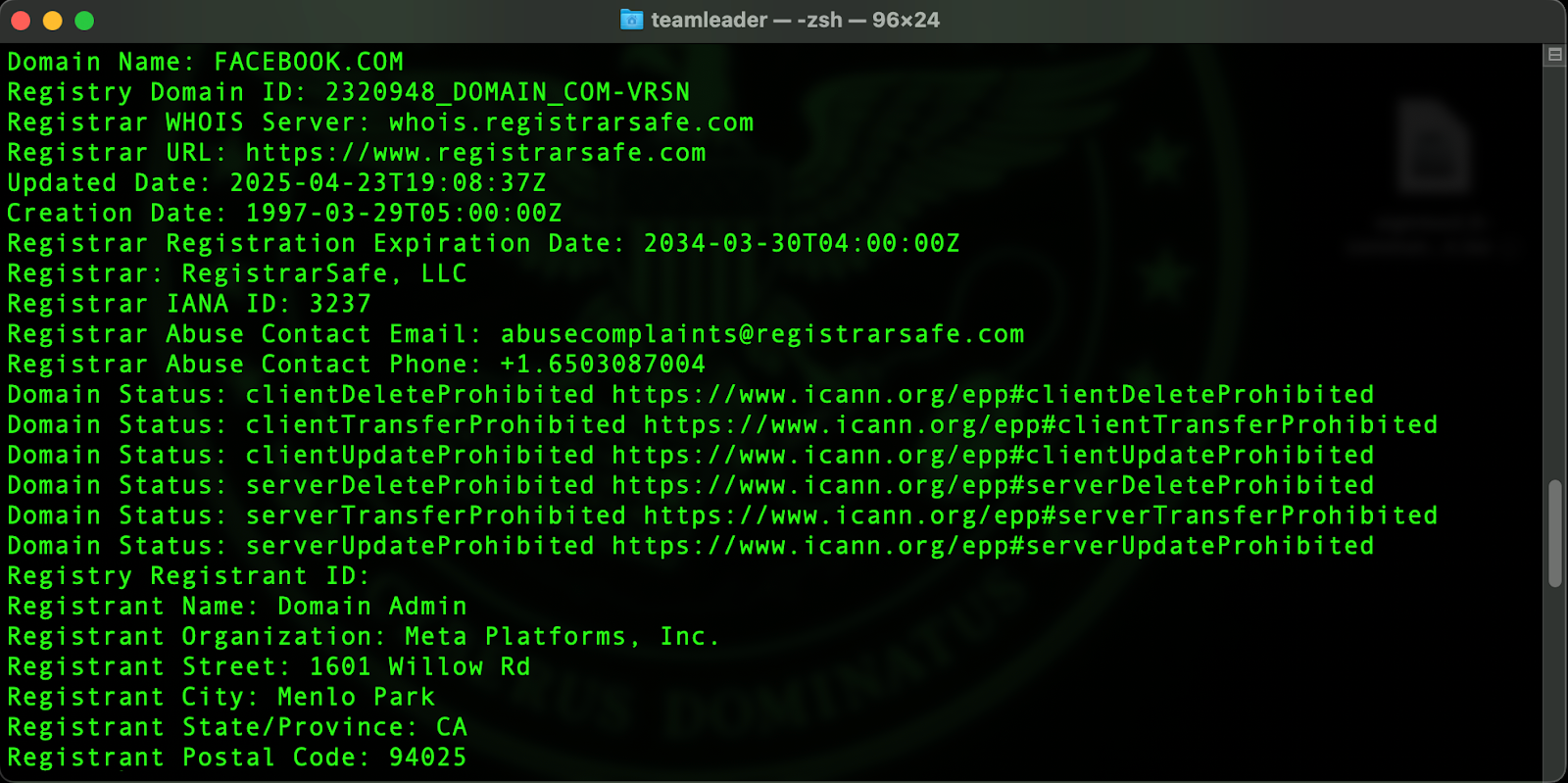

For macOS and Linux users, simply typing whois [enter URL here] will help you immediately inspect who owns any domain.